In 1792 real estate speculator Richard M. Woodhull purchased land surrounding North Second Street in Brooklyn, had it surveyed and then divided into city lots. His aim was to attract urban New Yorkers to what was then “the suburbs.” He established a horse ferry from the foot of North Second Street to Grand Street in Manhattan and opened a tavern. In 1800, he named the area Williamsburgh.

As it turned out, Woodhull’s business tactics were ahead of his time, and in 1811 he suffered financial failure. Subsequent ventures by other developers also failed – until roads were built in the early 1800s that connected the coast to the interior. Commuting became much easier, and interest in living and working in Williamsburgh increased.

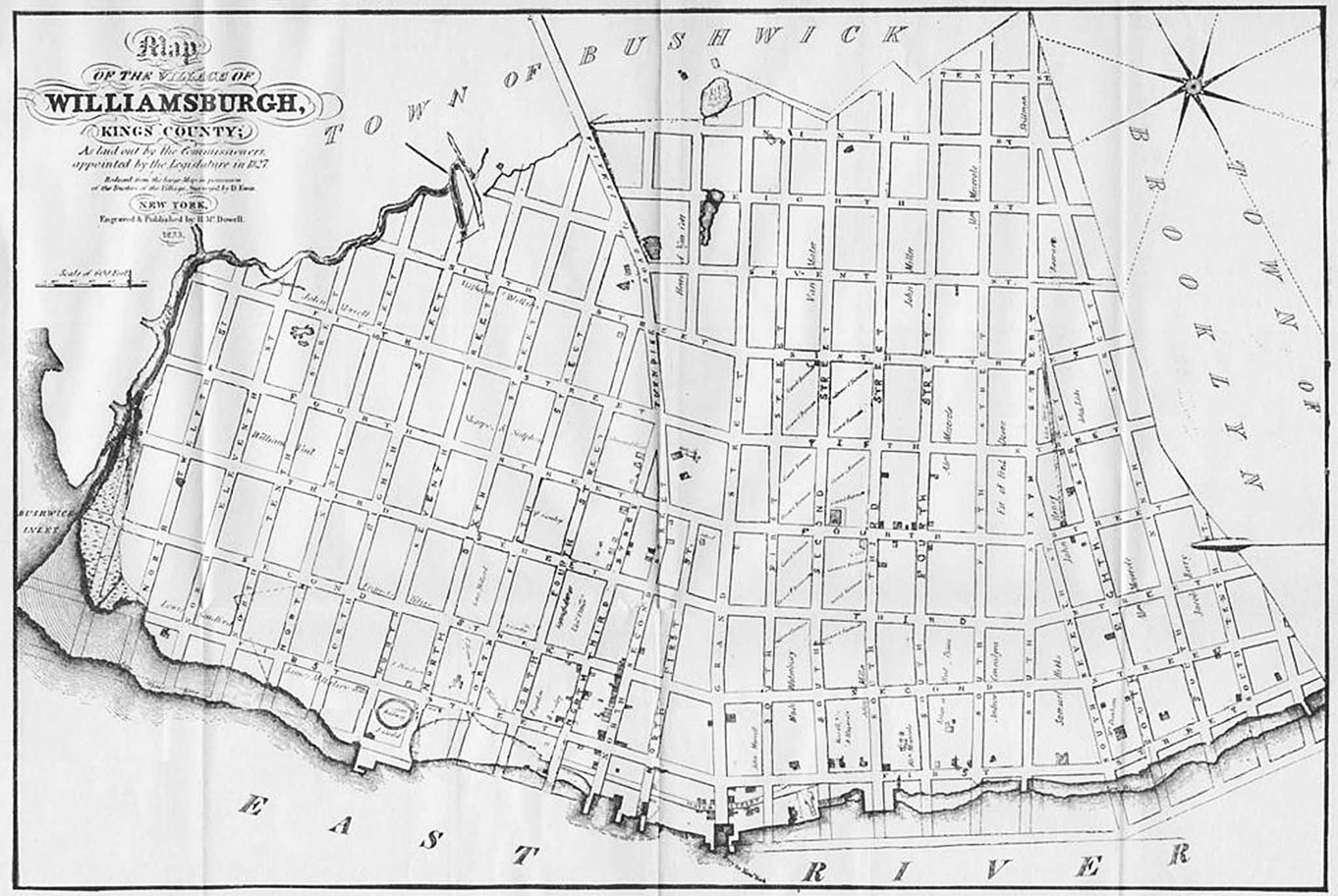

By 1827, Williamsburgh was incorporated as a village. A real estate crash in 1837 slowed development, but little by little, infrastructure was put in place to make Williamsburgh a city in its own right. On January 1, 1852, Williamsburgh received a city charter, but three years later it was consolidated into the City of Brooklyn. Upon consolidation, the “h” was dropped from the neighborhood’s name.

During the 1830s, Irish, German and Austrian capitalists established their businesses and homes in Williamsburgh. It became a fashionable resort that attracted such notables as Commodore Vanderbilt, Williams Whitney and railroad magnate James Fisk.

Some of the largest industrial firms in the nation grew here, such as Pfizer Pharmaceuticals (1849), Astral Oil (later Standard Oil), Brooklyn Flint Glass (later Corning Ware) and the Havemeyer and Elder sugar refinery (later Amstar and Domino). Breweries such as Schaefer, Rheingold and Schlitz as well as docks, shipyards, refineries, mills and foundries opened along the waterfront. In 1851, the Williamsburgh Savings Bank, Williamsburgh Dispensary, Division Avenue ferry and three new churches were established.

With the building of the Williamsburg Bridge in 1903, thousands of Lower East Side Jews crossed the river to make their homes in Williamsburg. Between 1900 and 1920, Williamsburg’s population doubled. Immigrants arrived from Eastern Europe, including Lithuania, Poland and Russia. A large number of Italian immigrants settled in the North Side.

By 1917, the neighborhood had some of the most densely populated blocks in all New York City. A single block between South Second and South Third Streets housed more than 5,000 persons. In the 1930s, large numbers of European Jews escaping Nazism fled to Williamsburg and established a Hasidic enclave.

From the mid-1930s to the 1960s, public housing projects replaced thousands of decaying buildings. In 1957, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway cut through the Williamsburg community (as well as Red Hook and Greenpoint), destroying huge numbers of low-income, single- and two-family homes.

With the 1960s came thousands of Puerto Ricans, drawn by the many factory jobs. Through the 1980s the Hispanic community grew to include Dominicans and other Latin Americans. In 1961 Williamsburg had 93,000 manufacturing jobs; by the 1990s, the number had decreased to less than 12,000. The decline in manufacturing left thousands of Hispanics unemployed.

In South Side Williamsburg, the Hasidic community continued to grow. Tensions increased between the Hispanic and Hasidic communities over government money and housing. In recent years, there have been some improvements in relations between these two groups.

Since the early 1990s Williamsburg has become home to a new set of “immigrants,” which has altered the face of the neighborhood. Many artists, writers and performers were attracted to the (comparatively) low rents and large light-filled lofts of Williamsburg’s former factories. Galleries, restaurants and shops opened to cater to these new residents, making it a destination for many 20- and 30-somethings with a distinct sense of style and earning it the nickname “hipster heaven.

The area traditionally called Williamsburg is today occupied mainly by the Yiddish-speaking Satmar Hassidim, who continue to wear the traditional dress of their ancestors in Europe and adhere closely to Jewish religious law. North of traditional Williamsburg is an area known as South Side, occupied by Puerto Ricans and Dominicans. To the north of that is an area known as North Side, traditionally Northern Italian, but now hosts increasing numbers of hipsters: artists and those who wish to associate with artists. So-called East Williamsburg is home to many industrial spaces and forms the largely black and Hispanic area between Williamsburg and Bushwick. Williamsburg, South Side, North Side, Greenpoint and East Williamsburg all form Brooklyn Community Board 1.

The hipster center of Williamsburg radiates from the strip of Bedford Avenue near the Bedford Avenue Station on the L train, the first stop from Manhattan. Since their settling in, ex-Manhattanites and hipsters from around the nation insist on calling their area Williamsburg, despite the fine distinctions natives make.

Find sleek styles, bold colors and cool graphics in [this] contemporary housewares shop. Nothing here is clunky or unwieldy, and most of the items fit just right in small apartments. Look for that perfect pop of color in Abode’s many bowls, serving trays, linens, bedding and rugs from eco-friendly brands like Goldiehome, Paper Cloud and Teroforma.

Continue readingBuilding Blocks: A Design Scene Grows in Brooklyn by Michael Silverberg, March/April 2010, page 44.

A trip to some of the latest and greatest in NYC design is just a short Town Car ride away. Abode New York: Bright and cheery modernism, from handmade industrial-felt bowls ($75) to inviting reclaimed-oak hooks ($20.50), is the order of business at this reasonably priced Williamsburg storefront.

Continue readingDesign Stores in Brooklyn. WILLIAMSBURG: Abode New York. If it is made by an up-and-coming Brooklyn designer (think Alex Gil Design, David Zachary, Domestic Aesthetic and White Bike Ceramics) and costs less than $75, it’s probably here.

Continue readingDesign Stores in Brooklyn. WILLIAMSBURG: Abode New York. If it is made by an up-and-coming Brooklyn designer (think Alex Gil Design, David Zachary, Domestic Aesthetic and White Bike Ceramics) and costs less than $75, it’s probably here.

Continue reading